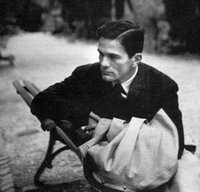

Pier Paolo Pasolini born 5 March 1922 (d.1975)

Pier Paolo Pasolini born 5 March 1922 (d.1975)Pasolini distinguished himself as a philosopher, linguist, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, newspaper and magazine columnist, actor, painter and political figure. He demonstrated a unique and extraordinary cultural versatility, in the process becoming a highly controversial figure.

Pier Paolo Pasolini is unquestionably one of the most important cultural figures to emerge from post-World War II Italy. But it is with film that he made his greatest impact.

Born in Bologna in 1922, Pasolini grew up in Friuli. While openly gay from the very start of his career (thanks to a gay sex scandal that sent him packing from his provincial hometown to live and work in Rome), Pasolini rarely dealt with homosexuality in his movies.

The subject is featured prominently in Teorema (1968); passingly in Arabian Nights (1974), in an idyll between a king and a commoner that ends in death; and, most darkly of all, in Salo (1975), his infamous rendition of the Marquis de Sade's compendium of sexual horrors, The 120 Days of Sodom.

Pasolini never saw himself as a 'gay artist'. Indeed, he explicitly rejected the assimilated gay middle-class he saw emerging just prior to his untimely death in 1975.

He began his career as a scriptwriter. When he broke out on his own as a writer-director with Accatone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962), he was apparently styling himself after the masters of Italian neo-realism, especially Roberto Rossellini.

But in 1964 he found his moviemaking 'voice' with The Gospel According to St. Matthew. With a non-professional cast and a quasi-documentary shooting style, Pasolini retold the familiar story of the life of Christ in the simplest, least-Hollywood-like style imaginable.

While its musical score was fairly avant-garde, featuring as it did excerpts from the African Missa Luba, Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky, and Mahalia Jackson singing Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child, the movie was accessible to audiences of all kinds.

Gospel was followed by The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), a comic fable about the adventures of a Chaplinesque father and son team, played by the great Italian star Toto and Ninetto Davoli, a young former lover of Pasolini's who was to appear in many of the filmmaker's works.

Not one to stick to the 'expected', Pasolini next turned to Sophocles' Oedipus Rex (1967), presenting the drama as a fable set in the wilds of North Africa and modern Rome.

After that came Teorema (1968), one of Pasolini's most controversial works, in which a sexual 'exterminating angel' (Terence Stamp) has his way with an entire Italian family.

Questions were raised when Pasolini cast Maria Callas in his rendition of Medea (1970), a film in which the legendary diva was not required to sing a note.

But a sudden turn of popular fortune came when Pasolini made The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974). They are as uncompromising as any of his films, but their comic spirit, frequent sexual interludes, and abundant nudity pleased moviegoers as no Pasolini work had done before.

And then came the posthumously released Salo. Most of the critics responded as though the horrors displayed in the film came directly from the gay Italian's feverish imagination. But all Pasolini did was extract selected passages of Sade and reset them in the last days of the fascist republic of Salo, the state-within-a-state established in the twilight of Mussolini's Italy.

And then came the posthumously released Salo. Most of the critics responded as though the horrors displayed in the film came directly from the gay Italian's feverish imagination. But all Pasolini did was extract selected passages of Sade and reset them in the last days of the fascist republic of Salo, the state-within-a-state established in the twilight of Mussolini's Italy.His most visually elegant and dramatically reserved work, Salo offers Sade's vision of old, wealthy, evil authorities (politicians, lawyers and bishops) having their way with nude and compliant youths and maidens of the lower classes as simply standard operational procedure for the powers that be.

Despite the outrage of some critics who complained of the director's decadence and depravity, the film actually presents a scrupulous version of the everyday reality of man's inhumanity to man.

Pasolini died on November 2, 1975 at the beach of Ostia, near Rome, in a location typical of his novels. He was murdered brutally by being run over several times with his own car. Giuseppe Pelosi, a hustler, was arrested and confessed to murdering Pasolini. In May 2005, he retracted his confession, claiming that unidentified men had killed Pasolini (he spoke of three strangers, with a southern Italian accent, insulting Pasolini as a 'filthy communist'). He gave threats of violence against his family as the reason for his erstwhile confession. The investigation into Pasolini's death was reopened following Pelosi's recantation.

His murder is still not completely explained: some contradictions in the declarations of Pelosi, a strange intervention by Italian secret services during the investigations and some lack of coherence of related documents during the different parts of the judicial procedures brought some of Pasolini's friends to suspect that his murder had been commissioned. An enquiry of Pasolini's friend Oriana Fallaci brought up the inefficiency of the investigations; many clues indicate as unlikely that Pelosi killed Pasolini alone. It is true, indeed, that Pasolini, in the months just before his death, had seen many politicians, telling them that he was aware of certain crucial secrets. Following Pelosi's statement of May 2005, the Rome police reopened the murder case; judges, however, considered the new elements insufficient to continue.

Evidence uncovered in 2005 points to Pasolini being murdered by an extortionist. Testimony by Pasolini's friend Sergio Citti indicates that some of the film rolls from Salò were stolen and Pasolini was going to meet with the thieves. He told others that he knew he would be murdered by the Mafia. Shortly after he was found dead.